Achilles Tendinopathy

But first, a disclaimer..

This blog post shares my experience dealing with Achilles tendinopathy, along with certain insights I felt were notable and perhaps interesting to others. I am not a medical expert/professional and I would strongly recommend you see a good physiotherapist as a first step when dealing with a tendinopathy.

A few years back I noticed the first twinges of an achy Achilles tendon. It started as a mild soreness only perceptible first thing in the morning but would progress into a rather debilitating injury. Fast forward to today, and now I don’t have the slightest twinge in the Achilles, even after running an ultra or slogging around in boots for days. The motivation for sharing my experience with this rather frustrating injury is to help others who are engaged in a similar uphill battle. Whether it is a tendinopathy of the medial epicondyle (climbers’ elbow) or of the midportion of the Achilles, the overall methodology of overcoming the injury is similar. These injuries develop over a long period, and as such they can take considerable time to overcome.

If you’ve got a sore Achilles, you’ve likely noticed its very reluctant to clear up on its own. It doesn’t take long to realize that rest is not conducive to improving tendon function. During the period of the rest, the tendon will often feel much better, but as soon as activity is resumed, the pain and dysfunction will be prompt to return. In the early phase of a tendon injury, it can be wise to back off activity for a short period, but it is imperative that progressive loading is resumed as soon as possible.

Classically, my tendinopathy started with a stiff tendon right after getting up in the morning. It was an easy injury to ignore. I hadn’t dealt with any real tendon injuries in the past and didn’t give much attention to this new morning ache. A few months later, it progressed into discomfort while running. My reaction was to simply take some time off running. As the winter season was approaching, it moved away from running for three to four months and focused on skiing. Returning to running in the spring, right away I noticed the achy Achilles once again.

A few months before the first race of the season in the spring, I started a program of heavy isometrics. The isometrics did help with the pain but not so much with the function. I was still struggling with flare ups even on shorter runs. I progressed the isometrics into the eccentrics as the months went by. I noticed marginal improvement week to week, but I still felt a long way away from pain free runs. Long story short, I didn’t end up doing any races that summer and instead spent a lot more time scrambling and climbing. Going into the next winter I was looking forward to spending more time on the skis. Unfortunately, my Achilles were now getting sore even in ski boots due to the physical pressure on the tendon. It had now been a year of this frustration.

By late winter I was fed up and really started to lean into this problem. I was making noticeable improvement by doing progressively heavier and heavier eccentrics. One evening while doing the exercise, I felt a sudden pop in my foot. I had torn my peroneal brevis tendon likely due to overloading it with the eccentrics. Now, I’d have to take off another few months while this healed up. Having this period off gave me plenty of time to dig into the research out there on tendinopathies. Functionally, my Achilles was preforming excellent by most metrics at this point. I could easily do fifty single leg heel raises and was preforming eccentrics with over sixty kilograms of additional weight. I was still struggling transferring this strength to running though and adding in plyometrics would be a key last step. Once my foot was healed up, I focused on a hopping program. With running, I cut the volume but added more short and fast efforts. In addition, I doubled down on strengthening the gluteal muscles, stretching and diet. By the summer I was back to running pain free. After a full season of many big days in the mountains including an Ultra race, I feel as though I’ve finally dealt with this injury.

Eric Carter stoked to be on the home stretch of the horseshoe traverse in Rogers Pass. At the time I was having difficulty trail running for much more than hour without flaring up the Achilles, but fortunately scrambling around was okay. Having other activities to switch to when you’re dealing with an injury goes a long way towards staying positive and maintaining fitness.

Owning Your Injury

This a slow degeneration injury of the tissue itself. It follows that there is something or several things in your routine or environment that is causing the tendon to degenerate. Many if not all of these things are modifiable. It is your job to find out exactly which of these factors are applicable to you. No expert in their field will be able to cover the full spectrum of variables which could contribute the degeneration. There is a lot of nuances to how these injuries can arise. Aches and pains in general are expected when you ask a lot out of your body. Fortunately, many of these tweaks simply sort themselves out without much trouble. It was my error to not sooner recognize the nature of my injury. Likely I could have had this problem behind me much sooner if I would have fully leaned into it right off the bat.

Eccentrics, Concentrics, Isometrics and Plyometrics

There is no shortage of information out there pointing towards eccentrics as the gold standard for rehabbing tendons. In 1998 Hakan Alfredson published a paper on the effectiveness of heavy-load eccentric training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendonosis [1]. This protocol involves one hundred and eighty repetitions preformed daily for an extended period with progressive increase in load. Three years later, a different loading protocol highlighting the effectiveness of both eccentric and concentric exercises for the treatment of Achilles tendinopathy was published [2]. Later, the benefits of isometrics were shared highlighting the immediate effect on pain and inhibition in patellar tendinopathy [3]. Most recently, Igor Sancho published a paper on the apparent effectiveness of hopping (plyometrics) as an intervention for runners with midportion Achilles tendinopathy [4].

The common theme amongst all the above protocols is tendons need load. The challenge is identifying what is the correct load. Jill Cook and Craig Purdam proposed a model that considers tendinopathy as a continuum [5]. Within this continuum there exists three stages: 1) reactive tendinopathy, 2) tendon disrepair, and 3) degenerative tendinopathy. Identifying where your tendon sits on this spectrum will assist you with a good starting point for how to load the tendon best. In addition, it is of critical importance that the load is applied consistently and progressively. Experimentation will be required to identify what will be most effective. My experience was that progressively starting with isometrics, into eccentrics/concentrics, followed up with plyometrics was effective. Perhaps if anything, the plyometrics seemed to have the greatest positive effect in returning to running.

Track running can be a great way to slowly increase both the intensity and duration of running. Unlike out-and-back runs or loops when you’re more likely to push a bit to far in order to complete the loop or get back. Tartan tracks also add a bit more of a forgiving surface to run on in comparison to concrete or asphalt.

Strength

General strength for both recovery and prevention are key. Weakness on the upper parts of the chain can create more force on distal areas of the body. Weak hip flexors can exasperate Achilles’ injuries. Hill sprints are in my experience of the most effective ways to build strength and power for running. As I started to develop Achilles tendinopathy, I backed off things like hill sprints and interval training with the idea it would rest the injury. In hindsight, cutting the volume of easy slow running may have been more effective while maintaining some specific running strength training. When I did finally reintroduce very short but hard efforts in the spring, I did notice continued improvements in my Achilles. As an added benefit, I did these efforts on a track, so it was easy to cut the workout short at the first sign I was possibly aggravating things.

It is important to integrate strength training into your program if you haven’t already done so. Carrying out maximal lifts is beneficial as it not only can strengthen the entire kinetic chain but also releases hormones that can stimulate the recovery of such as growth hormones and testosterone [6]. Pure physical strength protects against injury and adds resilience to correcting errors.

Get stronger. Incorporating strength work into your routine will go along way to both prevent injuries in the first place and improve performance. Split squats with a Bosu ball are a great exercise that add careful balance into strength training.

Strength training does place an additional load on the body, so if you’re already asking a lot of your body via high millage for example, it is important to correctly evaluate the merit of adding strength routines to your program throughout the year. Most importantly, it is imperative that you spend most of your time training for the activity you’re passionate about by doing that activity. All though not the most effective for moving large amounts of weight around, I enjoy bouldering to add in some strength work. The added benefit of bouldering is the complex movements involved and the pure fun of it. Learning how to try hard is key if you want to reap the greatest benefits. Trying hard at your maximal limit is a skill in of itself that requires development.

Diet

Tendons are made of what you eat. Tendons are not well vascularized in comparison to muscle tissue which is one of the contributing factors as to why tendons are slow to heal. The Achilles tendon is estimated to be composed of 90% type I collagen and as such requires ample

substrate for collagen synthesis [7]. Collagen syntheses is strongly dictated by the presence of amino acids, primarily; leucine, glycine and proline, taken together with vitamin C. It is critical to note the importance of vitamin C, as a deficiency results in scurvy, a disease characterized by a loss of collagen [8]. Improved collagen deposition and tendon strength has been observed when collagen is supplemented into the diet via gelatin, with a well-timed rehab program. In one clinical trial, it was found that ingestion of 15g of gelatin one hour before six minutes of jump rope was able to double collagen synthesis [9]. Gelatin contains the key amino acids conducive to collagen synthesis and is typically made from the skin, tendon and ligaments of cows or pigs. Supplementation of collagen can be advantageous, particularly if your diet is lacking in some foods. Natural foods that are beneficial to collagen health include bone broth, fish skin, chicken and organ meats along with berries, bell peppers and leafy greens. Bioavailability is generally superior when eating real food in comparison to supplementation.

Consider your daily intake of foods that are beneficial to collagen synthesis including fruits and vegetables that are high in vitamin C. Having the necessary substrates available to facilitate collagen production is essential, but in order to maximise the uptake of these amino acids and enzymes, well timed exercise in terms of duration and timing is key.

If you’re considering supplementing with collagen, I found this particular powder to be the only cost effective choice, which can be purchased at Costco. As noted, in order to maximize the benefits of collagen supplementation, you will want to be taking at least 15g in the both AM and PM, at a minimum along with 200mg of vitamin C.

Self Awareness

Becoming self aware is not only important to avoiding tendon injuries in the first place, but also in rehabbing injuries. Knowing when to back off during a session when a tendon is feeling tweaked will go a long way in keeping injuries at bay. Whether it’s trying that boulder problem one last time and hammering out a few more intervals, these are the times when causing a flare up is most likely. Improvement in any activity comes from consistency, which means keeping your body primed to put in the work, day after day without large periods of time off. It is always a better choice to cut a session short if there is even a chance of injury.

As discussed previously, progressively loading the tendon is the most important factor in stimulating healing. Tailoring this load appropriately is perhaps the greatest challenge. Either too little or too much load will be detrimental. Relative pain/discomfort during and post exercise needs to be astutely noted. Often in the early stages of a tendinopathy, pain will be minimal to non-existent during activity once the body warms up, but those first few steps out of bed out the next day are stiff and sore. If you can address a tendinopathy in the early stages, you’ll be able to manage it quickly without any big impacts to your regular routine. As the tendinopathy progresses, it is often accompanied by the innervation of the tendon with both blood vessels and nociceptors (pain sensing neurons). Therefore, the tendon becomes much more sensitive thanks to these new neurons that can be left behind even after the blood vessels disappear. This can result in a fully functional tendon that is still feeling sensitive. As a result, mild levels of pain will likely be experienced due to the mechanical stress imposed on the tendon load and exercising with mild pain can be beneficial to positive tendon adaptation. Tracking these pain levels is key, particularly noting the level of pain experienced 24hours post exercise. Monitoring if the pain is staying consistent, improving or getting worse. Mild to moderate discomfort (up to 4/10 on the pain scale) is generally considered acceptable during exercise and rule I followed. Often in the early stages of getting back to running I’d be at a consistent 2-3/10, which progressively improved as time went on.

Its human nature to misconstrue our niggles felt in the past relative to how we feel in the present moment. Writing down observation regularly helps to remove the bias that can inadvertently be applied to past experiences. When we’re going through a particularly tough patch, it is easy to remember the past in a negative light. Conversely, when things are going well, its common to only remember the good. Dealing with a tendinopathy effectively requires us to accurately recall times that were both good and bad in order to not repeat the same mistakes made in the past and to repeat the positive stimuli.

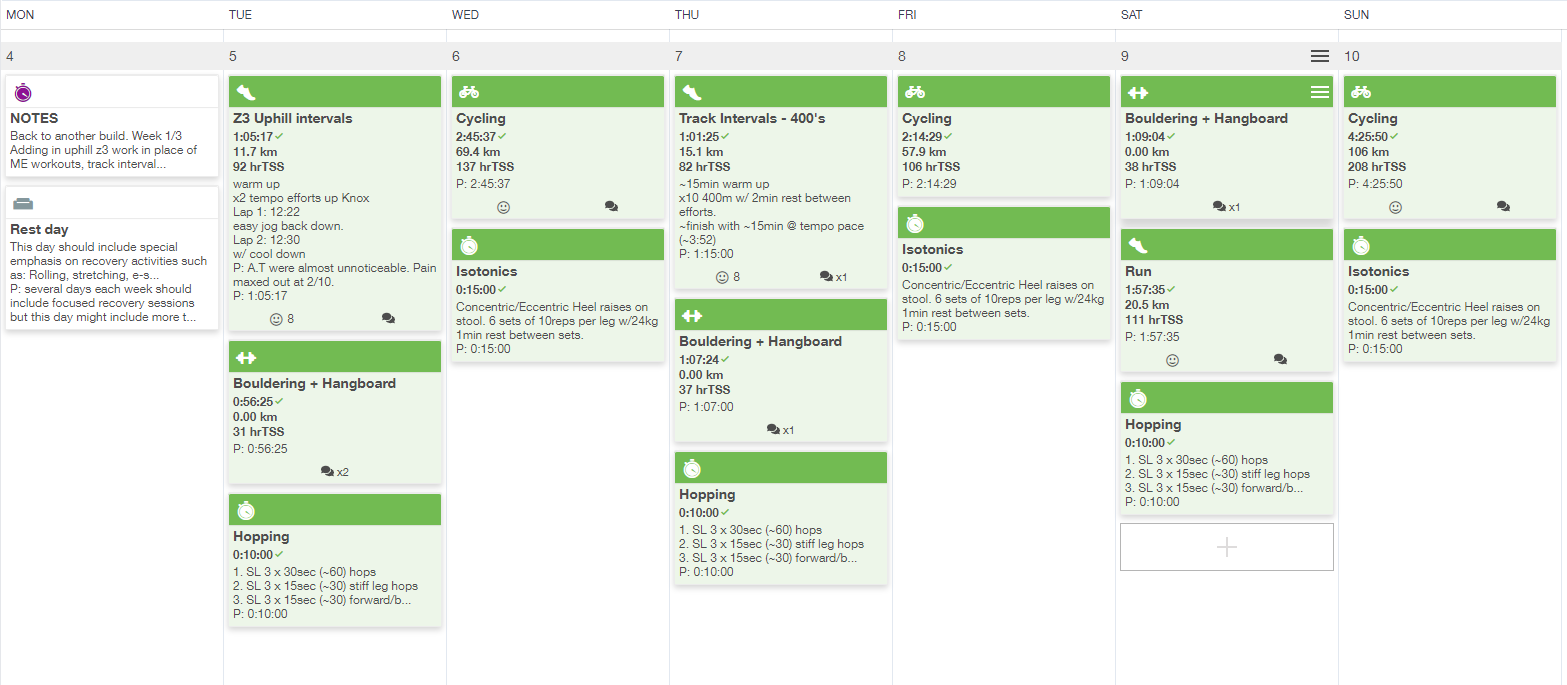

Start a training log. It takes all of a minute to make a quick note of what you’ve done each day. Having this information to look back on can be invaluable in figuring what may have lead to developing an injury in the first place. It is also a useful way to keep track of the rehab process and progressive loading.

Setting Expectations

Slow onset tendon injuries are slow to recover, consider that your recovery could be at least as long as the time that you have had the injury itself. Its not uncommon for chronic Achilles tendonosis to take a year to completely resolve itself. This does not mean you won’t be running for that duration, but rather it helps set expectations that prevent frustration when you’ve been persisting with a program for many months.

Don’t hesitate to revise you approach based on how you feel as you progress through a given protocol. Don’t expect the injury to heal completely overnight, but you should be able to note small but steady improvements week to week. Flare ups are to be expected from time to time but overall, a consistent improvement should occur.

Setting expectation appropriately will go a long way in maintaining a positive outlook throughout the process. Rather than putting on the pressure to get back for a particular race or event, consider taking an entire season off. Its important to look at the big picture when viewing injuries, in particular soft tissue impairments that can persist for many years if not indefinitely, without proper attention. Dialling things back for a year is nothing in the grand scheme of things but may be vital to a long healthy life pursuing you whatever activity motivates you.

Running out of gas on pitch three of Marriage Box in Echo Canyon. Fortunately, most common running injuries are not aggravated rock climbing. Not only is climbing awesome, but it goes a long way in developing general strength compared to traditional bipedal activities.

Photo Credit: Zac Colbran

Stretching

I’d be remiss not to mention the importance of stretching to some degree in dealing with a tendinopathy. I’ll be the first to admit I don’t have a good grasp on the science behind stretching, but I did note significant improvements after visiting a fascial stretch therapist. Admittedly, by the time I started to explore fascial stretch therapy I was through the worst of my Achilles Tendinopathy, however I feel that I should have pursued this treatment earlier. After just a few appointments and a short daily routine focused on stretching the posterior chain, I felt even further relief. I was at the point where it seemed impossible to flare up the Achilles anymore (note that I was still loading it via hopping at this point in addition to running). I suspect that by removing tension in the posterior chain, the Achilles was able to fully relax when it was not actively being used. There is some interesting reading out there regarding the different effects that both ballistic and static stretching appear to have on tendons [10]. Running imposes significant forces on the tendons due to the demand to rapidly store and release high loads as each foot strikes the ground, up 90-100 times per minute. To accommodate these high loads without sustaining damage, the Achilles tendon requires a high energy-absorbing capacity. Decreasing tendon stiffness has been shown to improve this energy capacity, which can be accomplished by ballistic stretching. It is important to note that a stiff tendon is also beneficial as it will be much more effective at transferring force. With this in mind, those pursuing ultra-distance running may be better served to have a slightly less stiff tendon.

Back at it. Happy to be pushing hard again at the Golden VK.

Photo credit: Simon Lee

References

[1] Alfredson H, Pietiläƒ T, Jonsson P, Lorentzon R. Heavy-load eccentric calf muscle training for the treatment of chronic Achilles tendinosis. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:360–6.

[2] Silbernagel KG, Thomee R, Thomee P, Karlsson J. Eccentric overload training for patients with chronic Achilles tendon pain--a randomised controlled study with reliability testing of the evaluation methods. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2001;11:197–206.

[3] Rio E, Kidgell D, Purdam C, et al. Isometric exercise induces analgesia and reduces inhibition in patellar tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2015;49(19):1277-1283. doi:10.1136/bjsports-2014-094386

[4] Sancho I, Morrissey D, Willy RW, Barton C, Malliaras P. Education and exercise supplemented by a pain-guided hopping intervention for male recreational runners with midportion Achilles tendinopathy: A single cohort feasibility study. Phys Ther Sport. 2019;40:107-116.

[5] Cook JL, Purdam CR. Is tendon pathology a continuum? A pathology model to explain the clinical presentation of load-induced tendinopathy. Br J Sports Med. 2009;43:409–16. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2008.051193.

[6] Kraemer WJ, Ratamess NA. Hormonal responses and adaptations to resistance exercise and training. Sports Med. 2005;35(4):339-361. doi:10.2165/00007256-200535040-00004

[7] Freedman BR, Gordon JA, Soslowsky LJ. The Achilles tendon: fundamental properties and mechanisms governing healing. Muscles Ligaments Tendons J. 2014;4(2):245-255. Published 2014 Jul 14.

[8] Peterkofsky B. Ascorbate requirement for hydroxylation and secretion of procollagen: relationship to inhibition of collagen synthesis in scurvy. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991;54:1135S–40S.

[9] Gregory Shaw, Ann Lee-Barthel, Megan LR Ross, Bing Wang, Keith Baar, Vitamin C–enriched gelatin supplementation before intermittent activity augments collagen synthesis, The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, Volume 105, Issue 1, January 2017, Pages 136–143,

[10] Witvrouw E, Mahieu N, Roosen P, McNair P. The role of stretching in tendon injuries. Br J Sports Med. 2007;41(4):224-226. doi:10.1136/bjsm.2006.034165